– The Tiananmen Square Massacre

by Julia H. Sun

THE AUTHOR: JULIA H. SUN

Like most days, I was going for my morning walk to buy food. Two buses were passing by.

I was shocked – the buses had chilling words written on them in blood:

“The government is killing students! Blood covered Tiananmen Square!”

The people on the street were huddled together. I heard their whispers:

“What happened in Beijing last night?”

“Did the government really kill students?

“Could this really happen?”

Like me, they don’t want to believe the government of Deng Xiaoping would do this to our own people.

I am a professor at the Civil Aviation Institute of China in Tianjin, a city about 90 miles from Beijing. I am teaching basic computer science and computer programming courses. There is a big shortage of professionals in every single field since there were not many colleges and universities after the Cultural Revolution. It is especially true for computer experts since computer technology is very new in China.

I was lucky and competitive enough to be able to get into college right after high school, at a time when less than 4% of the high school kids could go. I am assigned to the job right after I graduated from college with a computer engineering bachelor’s degree.

I have worked here for over a year. It is a great job, to most people, but not to me. I am not a very happy bird here. The school is in a very rural area. I feel the lack of connection to the outside world working there, and I don’t see a bright future.

My father and his generation worked in one job for life. I don’t plan to be a teacher at this college forever. I have ambitions. As a young lady just out of college, I want to see the world. I want to fly freely and fly high.

My parents never had that choice, but I do. I have a chance to go to the U.S. and I shouldn’t waste it. I have decided to go to the U.S. for over half a year now. The government corruption and civilian grievances only made me more eager to go to the U.S.

I went to the U.S. Embassy in Beijing and applied for a visa on Thursday, June 1. I was told by the U.S. Embassy that my visa was approved and I needed to pick up the visa at the embassy on Wednesday, June 6th.

It is noon. I leave home and take the school shuttle to the college, where I work as a professor in rural Tianjin. On the way, I don’t see any buses with the bloody words on the street anymore. After I get to the college in this Sunday afternoon, I hear a few college students have just come back from Beijing, and they are going to give a speech in the college auditorium in the evening.

I step into the auditorium. It is filled with one hundred people or more, mostly students, with some teachers, faculty members, and parents. While it is Sunday evening and on sudden notice, this group has congregated.

The two students on the stage are in tears… They saw what happened, they are crying for the students shot and killed. They are so disappointed in the government’s and the military’s actions.

The speech is short. But the impact is huge. Now everyone in the audience believes what we heard or the words we saw that morning on the buses.

It is not an easy evening for everybody, including me. It is too much for people to digest the information. Right after the meeting, people start to talk in groups with the others that they know well right outside the auditorium. I chat with other attendees, too. They question why Beijing killed students. They are concerned about what’s going to happen next. More military action?

Are we in danger?

I go back to my school dormitory room. My roommate comes in right after, with a middle-aged woman behind her. She is the mother of a student. She comes to the school to check whether her son is safe in school or is in Beijing with the protesters. As we are chatting, a few more teachers come to our room. A teacher, who has very close relatives in Beijing, tells us her parents were very worried about her uncle’s family there and called them. Her uncle’s family is safe and staying indoors.

It seems everybody in the room checked with their loved ones and is settled emotionally, at least at this moment. What is going to happen to all of us? What is going to happen to China?

What is going to happen to me?

I needed to pick up the visa at the embassy in Beijing in less than two days. The government has been shooting people and Beijing is occupied by the armed soldiers. Should I take the risk to go get the visa? If I don’t go, I might never be able to go to the US. I hear that the U.S. is considering closing the Chinese Embassy, possibly forever, if the Chinese government keeps killing innocent civilians. Beijing is occupied by the military and is unsafe for the U.S. embassy workers to stay. If I do go, I might get myself in the center of this turbulence, get gunshot or flying bullet, and then may never be able to go anywhere. No one can give me a firm answer. I must decide on my own.

The History:

I grew up in a very loving, caring, but poor family. I didn’t know anyone who had a lot of money.

When my mom was little, her family used to be very rich. Her family lived in the west part of Shangdong Province, about a three hours’ drive south of Beijing. All the relatives that had the same last name lived in the same village during that time. My mom’s family hired many people who worked for them on the farm and at home. But when my mom was still young, it was believed that a virus from the family cemetery spread quickly throughout this big family, killing most of the men and boys. My dad’s family was not as rich as my mom’s, but not very poor, either. My father’s father died in his thirties, while he was on a business trip. Nobody in the family knew how he died; he was on a boat sailing on the Yellow River. So my grandma raised her two sons on her own.

I heard there were wars all the time. The villages where my parents used to live always had different military groups pass by. They had to raise different flags for respective military groups when they passed by. In the 1930s, the Japanese troops occupied China and my mom almost got raped by a Japanese soldier. My grandma saved her. My dad needed to study Japanese in school.

After Mao took power, China became friends with the big Soviet Union. My sister was required to study Russian in school. The foreign language stressed in school depended upon which neighbor the regime in power was allied.

When Chairman Mao Zedong launched Cultural Revolution in 1966, he and his Communist Party removed traditional capitalist and cultural elements from Chinese society and imposed Maoist orthodoxy within the country.

People were all poor and had just enough food to eat. There were almost no salary changes, no inflation, and no ability to change jobs. There was few electric equipment or accessories at home, except a radio.

Even though there were public schools, many kids, especially the ones in the countryside, couldn’t go or finish their education. Education is not only useless but during that time also may cause trouble for you. Many educated people got criticized and forced to do hard farming labor to get “real education”.

Because my dad had many years of private education and did some work besides a regular job to make extra money to support the family of seven, they put him on stage with a hat on his head and criticized him in public for his “capitalist mind”. Not only he couldn’t use his education and skills as an advantage, he got criticized, did carpenter work, and paid a lower wage for his work – even though he did the most and the best job at work.

When the countryside kids finished school, they stayed at the farm. When city kids finished school, about half were sent to the rural countryside to get “educated,” after many school young people went wild causing troubles including killing many educated people during the Culture Revolution. The other half worked at an assigned job in a factory or in a service field such as butcher, cook or clerk. There was no college admission from high school. The very best students went to a nursing or technical vocational training school.

Only those who worked and had been “educated” very well, including military soldiers, were allowed go to college. The only person I knew who went to college was a girl from a neighboring family whose kids had a hard time making the passing grade in a regular public school. The people from the poorer or lower level of the society had a better chance to get in college.

When the district got college enrollment quotas, the district officials decided which local got the quota and then the local officials decided which person could enroll. The local government officials made the decision arbitrarily. The students could only tell school what they would like to do and which place or province they would like to go at the beginning of their last semester in college. But after that, they don’t have much choice of their own and might not get what they wanted.

I have been living in a time of historic change.

1976 was a shocking year in Chinese history. A big earthquake shook the land. One northeast city, Tangshan, was totally destroyed and many others including Beijing, the capital of China, and Tianjin, the third largest city in China, had many casualties. Coincidentally, the three highest government officials were sick and died, one quickly after another: Zhou Enlai, the Premier Minister; Zhu De, the top general of the Chinese army and one of the main founders of the People’s Liberation Army and the People’s Republic of China; and Mao.

After they died, Deng Xiaoping, using his influence in the army and the Communist Party, gained prominence in 1978 by outmaneuvering Mao’s chosen successor, Hua Guofeng. The new Chinese leadership of Deng abandoned Maoist-style planned socialist economics and opened China to market-oriented major economic reforms. The country focused on economic development.

The economic reforms opened a new era in Chinese history known as “Reforms and Opening up.” The goals of Deng’s reforms were the modernization of industry, agriculture, science and technology, and defense.”

Deng restored the University Entrance Examinations in 1977, opening the doors of college education to a generation of youth who lacked this opportunity during the Cultural Revolution. He elevated the social status of intellectuals from the lows of the Cultural Revolution to being an integral part of the reform. I was at the right time to attend college after I finished high school in 1983.

In the beginning of 1979, China and the United State formally established diplomatic relationships and Deng visited U.S. – the first official visit to U.S. by a Chinese Communist leader. It opened doors for both nations’ citizens to visit the other country. There are so many Chinese, especially Chinese college graduates who studied English in school and had some knowledge about the U.S., want to go to the U.S. and to experience the freedom there. There were a few colleagues at the college who went to the U.S. and told us how modern and advanced the U.S. was. This made me and many others at the college want to go there.

Mao’s regime allowed only state-owned enterprises. But many of them were being closed or privatized during the reform, leading to mass layoffs or downsizing. The influx of laid-off workers had no job opportunities since there was a lack of private and foreign businesses and capital. When students graduated from college, they used to get an assigned state job under Mao and it was still this way with the new Deng regime.

That’s how I landed at the assigned job at the college. The colleges contacted the respective state enterprises for the opening positions. Then they assigned their students to the positions available, according to the students’ school grades, hometown, and desired job locations. Most of the students went back to the same province they came from. But once the reforms took place, many state-owned businesses went private and there were not as many opportunities for the recent and prospective college graduates. This put more uncertainty into the future of the students and their families.

The central government had controlled supply and prices of goods until 1985. With Deng’s economic reforms, a two-track system was used. Some necessary goods, like commodities, were still under government control and other goods were now left to the vagaries of the free market. The same goods could have fixed and market prices depending on who purchased the goods: The government designated businesses got the low fixed price while all the rest got market price. Government officials had the authority to allocate or divert supplies to designated businesses. The officials sold supplies for their own profit. This official corruption is widely known as “guandao” where the government officials and their relatives profit. This continuation of guandao, when economic reforms were promised, made the people poor and angry. Double-digit inflation occurred, but wages were still state-controlled and didn’t change.

Experiencing a taste of freedom, the press began to report on issues they had never been able to cover before and students debated politics on college campuses. The free press made people more informed about by the problems and their causes; students’ debates led them to find ways to publicize their concerns.

It is the corruption, the overturn of the fifty years of stable Chinese society, and the unsynchronized reform transactions that lie at the root of the social dissatisfaction. People believed that the relatives of several prominent political leaders had generated huge personal wealth in business at the expense of the ordinary citizens.

Like big reforms throughout history, they brought huge ripples to still water. Too many changes occurred at too fast a pace; ordinary people were suffering in the process.

Many people started to complain in public. I saw a few of the very brave adults starting to give speeches at street corners and squares. At first, they disappeared right after a short speech to avoid government harassment or imprisonment. Later, as more and more people got involved, it became common to give speeches and demonstrate on the street. The demonstrators shouted slogans and carried banners with texts like “Down with corruption” and “Long live democracy.”

College students led most of the demonstrations. Student leaders gave the government their list of concerns, hoping the government leaders correct those concerns with the implementation of the reforms.

One of the few government leaders who was viewed as incorruptible and supportive to the demands of the demonstrators was Hu Yaobang, the former General Secretary of the Communist Party. But he was forced to resign his post by Deng and the other leaders. When Hu suddenly died from a heart attack in April 1989, it became the trigger event that led students and Beijing residents to mourn in Tiananmen Square and to revive calls among ordinary citizens to end government corruption.

Workers and peasants came to Tiananmen Square to protest and mourn Hu’s death. Calls for ending government corruption increased. Party leaders began to fear a people’s revolt. More and more people gathered in the square every day, putting increasing pressure on the government to take action.

(Note: The links on the dates below are the New York Times reporting on the events in China on that day.)

Monday, April 27: Ignoring government warnings of violent suppression of any mass demonstration, students from more than 40 universities began a march to Tiananmen. The students were joined by workers, intellectuals, journalist, monks, and civil servants.

The government initially attempted to appease the protesters through concessions, such as special talks and negotiations with student leaders. But the talks broke down. .A student-led hunger strike galvanized support for the demonstrators around the country. People from different social levels demonstrated in all major cities, including Shanghai, Tianjin, Nanjing, and Guangzhou.

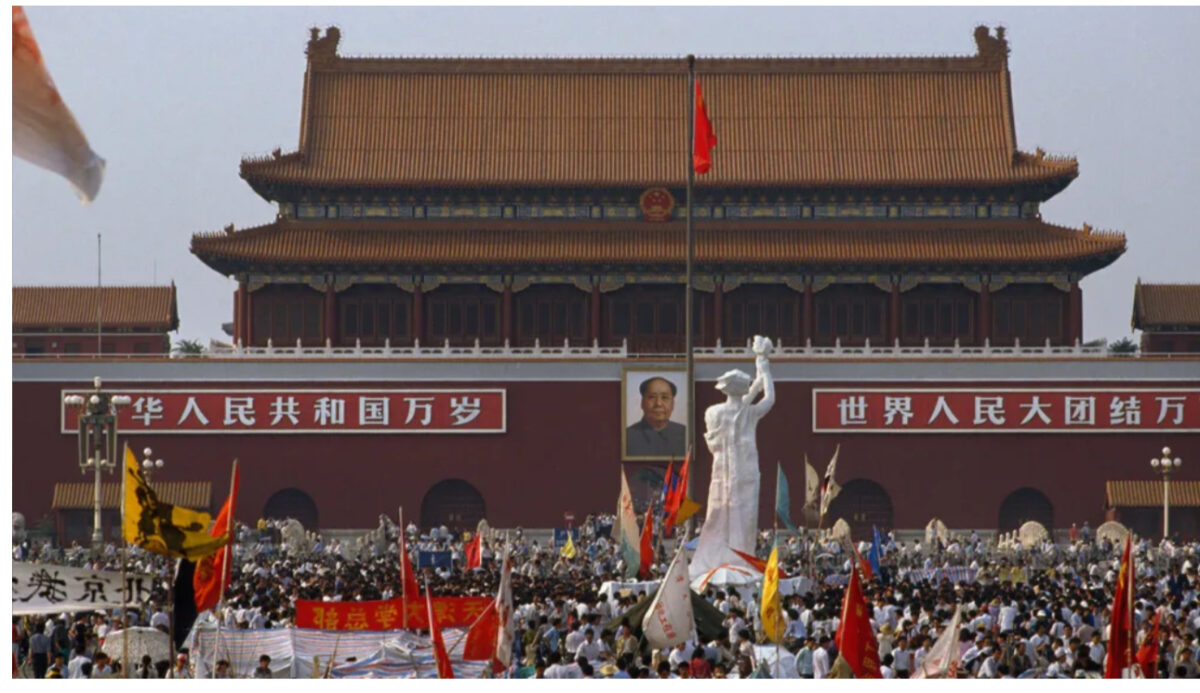

Saturday, May 13: The protest reached its peak, right before the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev visited Beijing. It is estimated that about 500,000 demonstrators assembled in Tiananmen Square.

Saturday, May 20: The government formally declared martial law in Beijing, and troops and tanks were called in to disperse the protesters in the city. However, large numbers of students and citizens blocked the army’s advance.

Tuesday, May 23: The government forces pulled back to the outskirts of Beijing.

Tuesday, May 30: The ten-meter-high Goddess of Democracy statue was unveiled at Tiananmen Square by the protesters. The students at Tiananmen Square were tired after a week-long hunger strike and occupying the square for over a month. Their flagging spirits were revived by the statue. On that day, a planned great demonstration and the statue attracted about 300,000 people to the square. The authorities angered and condemned the statue as an illegal structure that had to be torn down.

Thursday, June 1: I went to the U.S. Embassy in Beijing and applied for a visa. I was told by the U.S. Embassy that I needed to pick up the approved visa at the embassy on June 6th.

Sunday, June 4: The government killed the students and other demonstrators in fear of losing their positions and control in the very early morning.

Nicholas Kristof of the New York Times wrote:

Throughout the country, the love, fear and awe that the Communist Party once aroused have collapsed into something closer to disdain or even contempt. Young people used to dream of joining the party; now they often speak condescendingly of their peers who join. ”Me? A party member?” Cheng Lin, a 22-year-old woman who is one of China’s best-known pop singers, responded to a reporter’s question. ”Nobody joins the party now, among young people,” she cheerfully exaggerated….

Since 1985, according to The People’s Daily, 13 tax collectors have been murdered, 27 crippled and 6,400 beaten up.

Dissidents and student demonstrators have received most of the attention abroad, but among ordinary Chinese the practice of ignoring or defying the party has become nearly universal. For example, China propounds a ”one couple one child” birth-control policy, but in 1987 and 1988, according to Beijing University’s Institute of Population Research, Chinese couples could be expected to have an average of 2.45 children. The law also says women must be 20 and men 22 to marry, but as of 1986 (the last year for which the State Family Planning Commission has figures), more than a fifth of all marriages involved at least one partner who was underage; and in some remote areas these illegal marriages account for 90 percent of the total.”

Now the government of Deng is killing the demonstrators. There is no reason to stay in China during this turbulence.

The Obstacles:

I get back home the next day, on Monday, June 5. My parents, my sister, my brother and sister-in-law, and I all live in the same apartment. The apartment is small, has three rooms plus the separate kitchen area and a bathroom. But it is much better than the two rooms without kitchen area and with shared toilets we used to live in around a shared courtyard like most people who still live in a courtyard. My brother is married for just over a year now and is still waiting for the company he works for to assign his family a place to live. That’s how it works in a big city in China.

I tell them I have decided to go to Beijing to pick up my visa and am leaving home very early the next morning. My brother tells me he would go with me. I am very pleased that he plans to accompany me to Beijing.

I wake up in the morning and am getting ready to go. But I don’t see my brother. Finally, he comes out from their room and tells me it is too dangerous. His wife won’t let him go and I shouldn’t go either…

I decide to go by myself.

I get on the train to Beijing. A lot of people were on the train. It made me feel better to have company. But I am shocked that everybody gets off the train when the train reached the stop right before Beijing Station! Oh, my gosh! I am the only one in the compartment to go to Beijing! I can’t sit still anymore. I look out the windows. I see only freight trains with military covers and logos.

The train arrives at Beijing Station. I get off the train and walk into the station hallway. I look around and try to find company. The hallway is so big and so long and it makes me feel so tiny. I see nobody. I am the only person walking towards the station exit! As I walk closer to the exit, I see a guy sitting in his semi-manual foot-pedaled tuk-tuk right outside and next to the exit gate and a burning bus outside at the station square. This must be one of the buses that got burned by the angry citizens over the killing of innocent people!

Oh no! In the middle of the square, there is a soldier holding a gun! My head is bloated. This is really serious. I don’t think I should walk across the square all the way to the bus station as I did before. It looks too far a distance. I take the only tuk-tuk at the exit.

It is unbelievably quiet in the square. No more crowds and no more demonstrations, even no more people around. I hear only the sound of the tuk-tuk wheels. Oh, please, please make no more noise! But the wheels pay no attention to my worry. The military soldier hears the noise and turns his body towards me. His bayonet gun pointing right at me! My body is freezing with no breathing, and my heart is pounding. He stares to check me out. Suddenly, he turns his body back to the other way. Thank goodness, he turned the other way! I couldn’t wait for the tuk-tuk to pass by the station square and out of sight of the soldier.

I stand at the embassy door, frozen again. The sign on the door says the embassy is closed for safety reasons, because of the violence and killing of the last few days. It is unknown when they may open again if they do open again. I feel totally lost. I might never get my visa!

I drag my feet down the alley from the embassy. I got my passport easily from the Chinese government about half a year ago. I applied for the visa at the U.S. embassy several times. I didn’t give up after my visa applications got rejected by the embassy until finally, the embassy approved the visa on June 1. But I can’t pick it up now. What should I do?

I don’t see anybody in the alley, which used to be a very busy shopping street. The chaos in my mind can’t adjust to such a quiet alley because I don’t have my visa and I cannot do anything about it right now! But I do need to keep safe and get out of Beijing as soon as I can!

I get home, safely. For the next few days, I hear people talking about clashes and fighting among military units, troops fire shots near U.S. embassy apartments, and bullets shatter many windows and leave holes in the walls.

Friday, June 9: I was notified that the U.S. embassy had reopened, and I was going to be able to get my visa. I felt like I had waited forever. I made my air reservation to the U.S. right after I got my visa in Beijing.

Monday, June 12: I need an exit pass to get through Chinese customs. It was supposed to be easy to get an exit pass after you get your passport with the visa. I go to the passport agency at the district police department that morning. The passport officer informs me that I can’t get an exit pass without a letter from my college employer that I was not one of the demonstrators and do not plan to overthrow the government.

I rush to the bus stop and board the bus taking me to the college. I find the lady who is in charge of the security department in my school. I explain to her my situation and ask her for the verification letter. She pauses for a moment, staring at me. It makes me puzzled.

“I can give you the letter, but it has to be dated yesterday.”

“Thank you so much.” I seem to understand her, but I am confused why the date matters so much.

While she is preparing the letter, “We had a special emergency meeting this morning. It is ordered that no verification letter can be given out anymore!”

I dash out to the bus station right after I get the letter…

I wait and wait at the bus stop and bus is still not coming. More and more people come and wait at the bus stop. I feel it takes a century for the bus to come.

I get back to the district police station, showing them the letter. But now, they say they still can’t give me the exit pass!

We need higher authority – the police headquarters for the whole metro area – to approve that you are not in the demonstration. Here is the address of the headquarters office.

I need to go to the office to get another verification letter before they can give me the pass! The office is further from home and it is closing at 5 p.m. I look at my watch; it is 4:40 p.m. I had only 20 minutes left. There is no direct bus for me to ride. There are few cars in the city. I need to run to get there before the office close! I run and run and dash to the office, right before 5pm. Only one police officer is there. He is finishing up talking to another lady. I held my breath and hope nothing unexpected happens to me.

The officer faces me. “You don’t look strong and I don’t think you went to demonstrate, did you?”

“Oh, no, I didn’t and I won’t go. I want to go to the U.S. Why should I demonstrate?” I reply right away. He checks on my identification and gives me the letter, right before he closes the office door.

I need to rush back to the district police office again to get my exit pass before that office closes at 6 pm. I don’t know what is going to happen tomorrow. The government may give out another order saying “No more exit passes!” So I’d better finish all the paper work and get the exit pass today so I can go through customs!

My throat is so dry. I haven’t had one drop of water since 7 AM. But I get to go now and go fast. I get to the office before it closes. The lady works there already recognizes me. She checks the letters and my files and tells the guy across from her desk to give me the pass right away. She even says good luck to me, in a sincere whisper. So I finally get the pass!!!!!!

I get home in the evening. I feel so relaxed at home after I got all the paper work needed. Everybody in the family already had dinner. I’m so starving and having the best meal in my life.

Thursday, June 15: I get cash from family and on the way to Beijing to check out my air ticket. The ticket hall is packed with people; most of them are there for international flights. Since I work for the Civil Aviation Institute of China and know many people at Civil Aviation Authority Buildings there through colleagues and many visits to the buildings, I don’t think I would have any trouble to get a ticket.

I am at the ticket counter and the lady is checking out my ticket. The ticket is taken, and she couldn’t finish checking out for me. Somebody takes my ticket while we are checking out! The only people who can do this are the ones working in the Central Control Office. They can change a person’s name for the ticket in the computer and then issue the ticket to another person. So many people are trying to get out of China, both Chinese and other nationalities, right after the crackdown. But there are not enough flights available and people are trying very hard to get their tickets. The clerk knows me though a couple of friends. She rushes to the Central Control Office in the same building and gets the ticket back before it is issued to another person.

June 16 through 25: I have my exit pass; I get my air ticket; I do shopping and packing; and I take some time to say goodbye to my friends, relatives, colleagues, and family.

Tuesday, June 27: All my close family members in the city get in a van to send me off, except my dad. He is not in good health. While the van starts moving, I turn my head, wave to him, and take a last look at him through the back window of the van.

I get to Beijing International Airport and stay at the airport employee dorm for the night. I’m in the air to the U.S. the next morning.

Wednesday, June 28: It is a long flight over the ocean. Finally, the other passengers and I see the land as the plane approaches San Francisco. People in the flight are so excited and many crowd to the windows. Through the windows, I see the land with many cars moving along the highway. My dream of free land comes true, and I’m going to have a new journey of life in a new country.

I have come to the U.S. from China, in the midst of the Tiananmen Square crackdown. I have overcome many obstacles from the Chinese government to prevent this trip. But it is my dream to experience the freedom and opportunity that is available only in the U.S. I have persevered and won.

I’m happy I have come to the US. At the same time, I’m thinking, “When can the people in China have a voice and the history of the crackdown be told and redressed…”

Epilogue:

I couldn’t return to China until I got my US green card in 1994. If I did return, I had the risk that I couldn’t get out from China or enter the US again. Both Chinese and the American governments controlled much for the people coming and going during that time. Sadly, my dad passed away in 1992. My family didn’t tell me when he was sick in the hospital. They didn’t want me to be sad and worried while I was pregnant with my first baby. I couldn’t go back to see him while he was really sick and dying even after I heard about it. I couldn’t talk to him, either.

There is no phone at home and at the hospital for patients. I had to call my brother-in-law at his work since that was the only place that can receive international phone calls for the big family. Or they had to go to the only international long distance service office in the city that was far away to make collect calls to me. I sent letters to them for most communications. I missed my dad and the whole family. My dad took care of the farmland for the family before he moved to the city, and worked at a steel factory as a carpenter until he retired.

I have two sisters and two brothers. One of the brothers had to go to countryside from the city to get “educated” during the culture revolution. My dad retired early to give the position at the factory to my other brother so the brother could work right after he finished school. One of the sisters had to pretend to be sick to avoid going to the countryside after she graduated from high school. It was always the sister who wrote letters to me for the family. My mom and her oldest son and daughter never went to school when they were young.

The Chinese government is still avoiding talking about the incident, and many families are still sobbing privately about their loved ones who got killed. Nobody knows how many people got killed or wounded. Estimated range from hundreds up to 3,000.

Coming to a new country and environment, I faced many new challenges, like most immigrants do. But that didn’t and will never stop me from pursuing my dreams. They can only make me grow stronger with the many experiences I went through.

Copyright 2013 – 2025 Julia H. Sun. All rights reserved.

This is the right blog for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually would want,HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic that’s been written about for years. Great stuff, just great!

Thank you for your comment. People outside China only saw the Tiananmen Massacre on TV, witnessing the tragic events at the Square without fully understanding its profound impact on all Chinese citizens. My post aims to shed light on the truth of the event and its effects on ordinary lives. Even as someone who typically avoids political involvement and didn’t participate in the demonstrations, I was deeply affected.

Thank you for your comment. People outside China only saw the Tiananmen Massacre on TV, witnessing the tragic events at the Square without fully understanding its profound impact on all Chinese citizens. My post aims to shed light on the truth of the event and its effects on ordinary lives. Even as someone who typically avoids political involvement and didn’t participate in the demonstrations, I was deeply affected.

Hi Julia,

Glad to learn more about the incident and what living in modern China is like for some people. I prefer to think of ancient China with all of those temples with monks practicing Qigong and meditation.

The Falun Dafa qigong propaganda has tried to make the West think that Tinamen Square was a reaction by the government to stop the Falun Dafa movement. Your article has debunked that slanted view.

Thank you for taking the time to read the article and share your reflections. China does have a long and rich spiritual history rooted in Daoism and traditional cultivation practices, and it’s understandable that many people are drawn to that vision of ancient China.

My intention in writing this piece was simply to describe my personal experience of modern China and to place certain historical events in their proper context. One point that often causes confusion is that the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and the later Falun Gong–related demonstrations in the 1990s were separate events with different causes and timelines, even though they both involved the same physical location.

I’m glad the article helped clarify that distinction and contributed to a better understanding of how modern history, politics, and lived experience can differ from spiritual or cultural ideals.

As you noticed, Falun Gong is a very unsafe exercise to practice and many of its practitioners get into mental health problems because it unsafely makes people use higher energy. It is called energy deviation. Similar practices keep happening in history and nowadays.

Thank you again for engaging thoughtfully with the post.